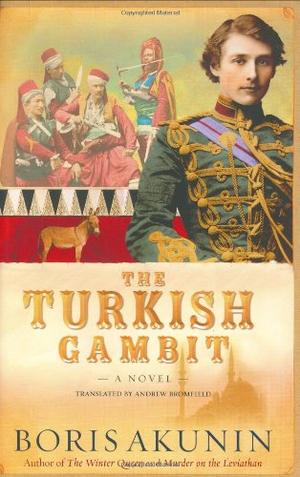

In Boris Akunin's The Turkish Gambit, Russo-Turkish war correspondent Seamus McLaughlin, tells his French counterpart Charles Paladin that a writer needs something interesting to happen before he can tell a good story. Paladin disagrees, and proves his point by writing his next story about a mundane object of McLaughlin's choice.

La Revue Parisienne

18th July 1877

Charles Paladin

Old Boots - A front-line sketch

Their leather has cracked and turned softer than the skin on a horse's lips. In such boots one could not possibly appear in respectable company. And of course, I don't - the boots are meant to serve a quite different purpose.

They were sown for me ten years ago by an old man in Sofia. As he fleeced me of ten lire, he said: 'Monsieur, long after the burdock is growing thick over my grave, you will still be wearing these boots and remembering old Issac with a kindly word.'

Less than a year passed before the heel of the left boot fell off in the excavation site of an Assyrian city in Mesopotamia. I was obliged to return to camp alone. As I hobbled across the burning sand, I cursed that old swindler from Sofia in the vilest possible terms and swore I would burn those boots on the camp fire.

The British archaeologists I was working with never did get back to the camp. They were attacked by the horsemen of the Rifat-bek, who regard all infidels as children of Satan, and every last one of them was butchered. I did not burn the boots; instead I replaced the heel and ordered silver heel plates.

In 1873, in the month of May, while I was on my way to Khiva, my guide Asaf decided to appropriate my watch, my rifle and my black Akhaltekin stallion Yataghan. At night, while I lay sleeping in my tent, Asaf dropped a carpet viper, whose bite is deadly, into my left boot. But the toe of the boot was gaping open and the viper crawled away into the desert. In the morning Asaf himself told me what had happened because he saw the hand of Allah in it.

Six months later, the steamship Adrianople ran on to rocks in the Gulf of Therma. I drifted along the shoreline for two and a half leagues. The boots were pulling me down to the bottom, but I did not take them off, for I knew that act would be tantamount to capitulation, and then I would never reach land. Those boots gave me the strength not to give in. And I was the only one who made it ashore; everyone else was drowned.

Now I find myself in a place where men are being killed. The shadow of death hangs over us every day. But I am calm. I put on my boots, which in ten years have changed their colour from black to red, and even under fire I feel as though I am gliding across gleaming parquet in my dancing shoes.

And I never allow my horse to trample burdock - just in case it might be growing over old Isaac's grave.